What Does Tutoring Have to Do With MTSS?

There are many important components to a successful implementation of a Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) framework. All components of MTSS are interconnected and inform one another. (See this MTSS flowchart for a visual overview of the framework.)

Tips for Effectively Leveraging Tutoring and MTSS

|

One core component of the MTSS process is the responsibility to connect students performing significantly below grade level with effective interventions. While tutoring itself is not an intervention, the evidence-based strategies, programs, tools, and instruction utilized during the tutoring session are interventions. Let’s take a look at how tutoring can be used to support MTSS in a school or district.

Is Tutoring Effective?

Tutoring is a format for delivering interventions. The goal is to connect students with effective interventions that help to close gaps. The best way to find out whether or not an intervention is effective is to consult scientific research. One of the first steps in selecting an intervention is to determine how and when this intervention will occur. So, that begs the question...

Is tutoring an effective method of delivering interventions?

A recent meta-analysis of 96 studies found consistently large improvements as a result of tutoring. The gains seen essentially “translate to a student advancing from the 50th percentile to nearly the 66th percentile.” Documenting similar results, a meta-analysis involving children from low socioeconomic status found that tutoring was the most effective way to structure an intervention, ahead of feedback/progress monitoring and cooperative learning.

Of course, not all tutoring programs are created equal. We’ll delve more into the components of a successful tutoring program in the following sections.

Who Makes an Effective Tutor?

Professional or paraprofessional teachers generally make the most effective tutors. A meta-analysis demonstrated the biggest positive impact from teacher-led tutoring, followed by paraprofessional-led programs. The parent or volunteer-led programs were the least effective, although they still yielded positive gains.

It can be intimidating to imagine staffing these tutoring groups with professional teachers, especially considering recent teacher shortages. Teacher staffing challenges have led researchers to explore other options.

The Hamilton Project researched a math tutoring program involving more than 2,700 students in 12 Chicago Public schools. In these programs, the math tutors were recent college graduates or people interested in public service.

The study documented large, positive impacts. Students who participated were compared to similar peers who had not. Tutored students were 50% more likely to pass their math class. Unexpectedly, they were also 28% more likely to pass non-math classes! The researchers estimated that the math intervention equated to approximately an extra one to two years of math instruction.

These promising results happened with trained volunteers as tutors. It’s encouraging to recognize that, in order to obtain strong positive results, a degree in education is not necessarily needed for tutors. In this study, the volunteers underwent ongoing coaching and mentorship from teachers. While utilizing certified interventionists is the most effective delivery method for delivering intervention, trained tutors can also provide a solid support structure for students needing additional academic support—especially when faced with staff shortages.

How Often Should Effective Tutoring Take Place?

In the Hamilton Project, sessions happened every school day for 50 minutes. This is certainly an intensive method for delivering intervention. Studies suggest that “high-dosage tutoring”—defined as tutoring that happens three or more times per week—is the most effective form of tutoring.

Similar to recommendations for frequency of interventions, this high-dosage strategy makes sense. If all kids need repeated practice to learn a new concept, wouldn’t this be even more true for students who struggle? Though intensive tutoring can be costly in terms of time and resources, this scheduling pays off. One study found that high-dosage tutoring was, on some measures, more effective than early childhood intervention.

Some tutoring structures depend on a “tutoring day,” where students receive tutoring only one day a week. A “tutoring day” is often used as a school-wide implementation model, where tutoring happens only once a week. While this is definitely one of the easiest options for tutoring implementation, there is little evidence that once-per-week tutoring leads to significant gains. Consistent and frequent tutoring allows students to receive more support for longer periods.

How Many Students Should There Be Per Group?

While structuring students will depend on the level of need of each student as well as the particular intervention being used, a variety of grouping structures could be used in a tutoring setting.

The instructional groups studied by the Hamilton Project matched two students to one tutor. Some studies suggest that groups can be effective for up to three or four students. The Education Endowment Foundation, a nonprofit in the UK researching education, stated that the ideal group size is two to five students.

Students who are grouped in tutoring should have matching identified skill deficits or needs. This maximizes the efficiency and effectiveness of the tutoring session and ensures that students are receiving appropriate skill-matched interventions.

Smaller groups consisting of one-on-one pairings will allow instructors to give each student more attention and feedback. This level of support is most appropriate for students needing Tier 3 intervention. Larger groups of two to five students allow for more cooperative learning and are less resource-intensive. This may be a great fit for students needing Tier 2 intervention.

Can Tutoring Be Utilized To Facilitate Both Reading and Math Interventions?

Studies show that tutoring is an effective tool for implementing intervention for both reading and math skills. Efficacy seems to vary by subject and grade level. For example, reading tutoring tends to be most effective for preschool through first grade. Math tutoring tends to be most effective for second through fifth graders.

When Should Tutoring Take Place?

Many programs take place after school, but the students who most need to participate may not be able to access services outside of the regular school day. It can be difficult to organize transportation after buses have already run. Parents may also perceive tutoring as a supplemental, nonessential activity if it takes place after school.

A study by Brown University suggested that tutoring during the school day is about twice as effective as before or after-school services. To make this happen, another article from Brown University suggests that tutoring “happens daily, for a full class period, during the normal school day. Not after school, when kids are desperate to head home.”

Is Tutoring Too Expensive?

With small group sizes and several sessions per week, some may question whether this is a sustainable strategy.

Americorps conducted an analysis of Minnesota Reading Corps, a large-scale reading program for students in kindergarten through third grade. They found that, for every dollar spent, approximately $5.47 to $6.99 dollars were saved. The kindergartners who participated had higher high school graduation rates and increased employment earnings. They concluded that the benefits were at least five times greater than the cost.

The Hamilton Project found that students who participated were likely to make $700 to $1050 more each year than those who hadn’t. They estimated that the benefits resulting from their higher earnings were five to eleven times greater than the cost.

The long-term ROI of tutoring interventions often far outweighs the upfront investment.

What Materials Are Needed to Implement a Tutoring Intervention?

Tutors should use high-quality, research-based instructional content. It’s important to note that giving a student simpler, below-grade-level material is likely to leave them falling further behind.

Selecting instructional and intervention materials is one of the most important parts of implementing a tutoring program. To help select research-based materials, you can consult resources such as the What Works Clearinghouse and the National Center for Intensive Intervention.

Tutoring does not replace the need for a strong core curriculum. The activities planned in a tutoring session need to align with and support the material being covered during Tier 1 instruction.

How Do I Know if Tutoring is Working?

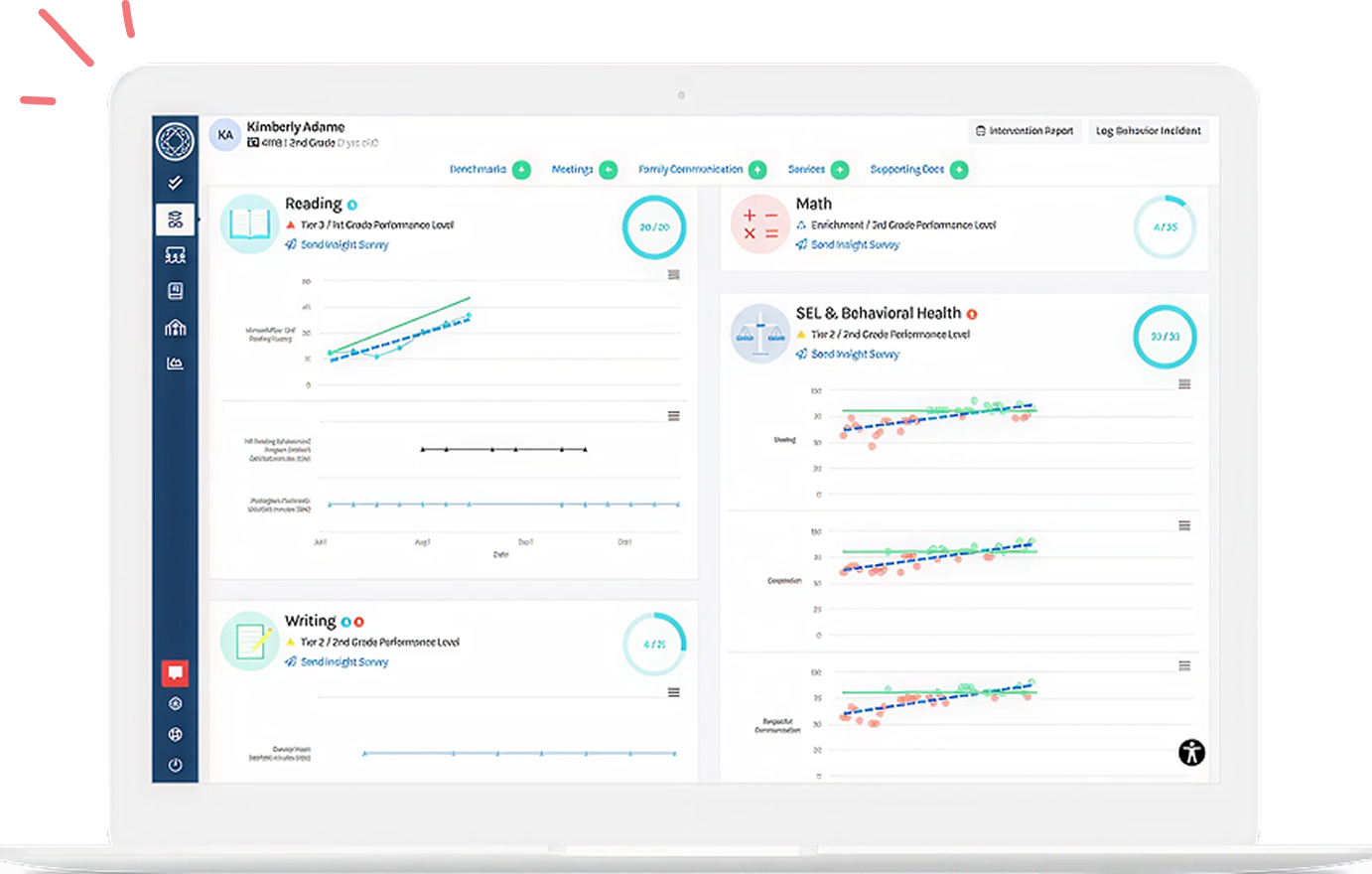

Like all MTSS interventions, it’s important to keep data on student progress. Data-based decision-making contributes to the ongoing feedback loop of MTSS. Universal screenings help identify students who need Tier 2 and Tier 3 support. MTSS teams connect these students with effective interventions. Ongoing data collection methods, such as progress monitoring assessments, show us whether or not the intervention is working.

EdResearch for Recovery found that the most effective tutoring programs regularly and continuously collect and evaluate data to improve their programs.

How To Implement Tutoring Within an MTSS Framework: From Research to Practice

There are many variables to consider when organizing a tutoring intervention for your students. Every district will have different needs, but generally, the best practices are:

- Creating groups with small student-to-tutor ratios (maximum of 4-5 students per tutor)

- Utilizing teachers or paraprofessionals as tutors

- Ensuring support is intensive enough to meet student needs (usually at least 3 sessions per week)

- Scheduling tutoring during the school day

- Selecting high-quality research-based instructional materials

- Keeping ongoing data and using the data to shape your intervention

Help Your Students Achieve Academic Success with Branching Minds 💪

![[Guest Author] Laura Reber-avatar](https://www.branchingminds.com/hs-fs/hubfs/Graphics%20for%20blog%20content%20and%20promotion/laura-reber-headshot-cropped.png?width=82&height=82&name=laura-reber-headshot-cropped.png)

About the author

[Guest Author] Laura Reber

Laura Reber is a school psychologist who graduated valedictorian from Truman State University before completing her graduate degree in School Psychology from Illinois State University. She has worked as a school psychologist for over a decade, leading special education and MTSS teams. She also founded a tutoring company that has provided high-quality interventions to hundreds of students with a variety of academic needs. She serves Branching Minds as a consultant bringing together her knowledge of special education, MTSS, and effective academic and behavioral interventions. She loves to work with schools across the nation to implement effective MTSS systems because she has seen the power of MTSS in improving outcomes for students and schools!

Your MTSS Transformation Starts Here

Enhance your MTSS process. Book a Branching Minds demo today.

.png?width=716&height=522&name=Tier%203%20Behavior%20Support%20Planning%20(preview).png)