During a parent-teacher conference, as I was explaining a child's assessment scores and grades, the parent interrupted me in confusion. “I don’t understand. They have an A in your class but can barely write a sentence, and their reading score isn’t that high.” As a young teacher, I stumbled through my answer, realizing that the way that we weighted grades meant that the work that students did in class was graded based on completion and re-takes. These grades often did not align with the results of the standardized assessments we gave. I knew at that moment that my grade book needed a revamp to reflect mastering the standards for the grade level.

What Are “Standards” and Where Did They Come From?

![]() The Common Core State Standards (CCSS) were created to bring consistency and transparency to what kids are learning across the United States. The initiative was born out of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, which required schools to show progress on state assessments or face additional accountability. The Council of Chief State School Officers, the nonprofit education reform group Achieve, and former Arizona Gov. Janet Napolitano collaborated to establish a set of specific skills (standards) at each grade level that students must master by the end of each school year (Bidwell, 2014). Initially, CCSS only covered math and reading, but they have since expanded to include other subjects such as social studies, science, art, and social-emotional learning.

The Common Core State Standards (CCSS) were created to bring consistency and transparency to what kids are learning across the United States. The initiative was born out of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, which required schools to show progress on state assessments or face additional accountability. The Council of Chief State School Officers, the nonprofit education reform group Achieve, and former Arizona Gov. Janet Napolitano collaborated to establish a set of specific skills (standards) at each grade level that students must master by the end of each school year (Bidwell, 2014). Initially, CCSS only covered math and reading, but they have since expanded to include other subjects such as social studies, science, art, and social-emotional learning.

The goal is to move away from traditional report cards with letter grades to a standardized system of grading that reflects what each student actually knows and can demonstrate. For example, a student with excellent behavior and participation in class and every assignment complete may not have mastered the academic content. This is tough to recognize when so many variables contribute to a traditional A-F grade.

What is “Mastery?”

![]() CCSS-based report cards replace traditional grading by reflecting mastery over specific skills. A student might earn a 1 (beginning), 2 (making progress), or a 3 (mastery) for each of the skills taught. Within one unit, a student may learn several standards. Upon completion of the final assessment, each question associated with a particular standard would reflect mastery of a skill. If a student earned 16 out of 20, that is considered 80%, likely a B on a traditional scale. If the four wrong questions assessed the same standard, then the student did not demonstrate mastery of that standard. Instead of retaking the entire test, a student may have additional practice and assessment opportunities to demonstrate mastery over the specific missed skill. With standards-based grading, students have multiple opportunities to learn rather than the traditional “teaching, assessing, and moving on” approach.

CCSS-based report cards replace traditional grading by reflecting mastery over specific skills. A student might earn a 1 (beginning), 2 (making progress), or a 3 (mastery) for each of the skills taught. Within one unit, a student may learn several standards. Upon completion of the final assessment, each question associated with a particular standard would reflect mastery of a skill. If a student earned 16 out of 20, that is considered 80%, likely a B on a traditional scale. If the four wrong questions assessed the same standard, then the student did not demonstrate mastery of that standard. Instead of retaking the entire test, a student may have additional practice and assessment opportunities to demonstrate mastery over the specific missed skill. With standards-based grading, students have multiple opportunities to learn rather than the traditional “teaching, assessing, and moving on” approach.

| The goal is to learn the skill, not earn a grade. |

While many schools still maintain traditional report cards, more and more schools are adopting standards-based reporting, and nearly all states have integrated CCSS into their curriculum planning. Most publishers align their curricula to these standards as well. The country has a way to go on the CCSS journey, but it has come a long way toward making education more consistent and transparent nationwide.

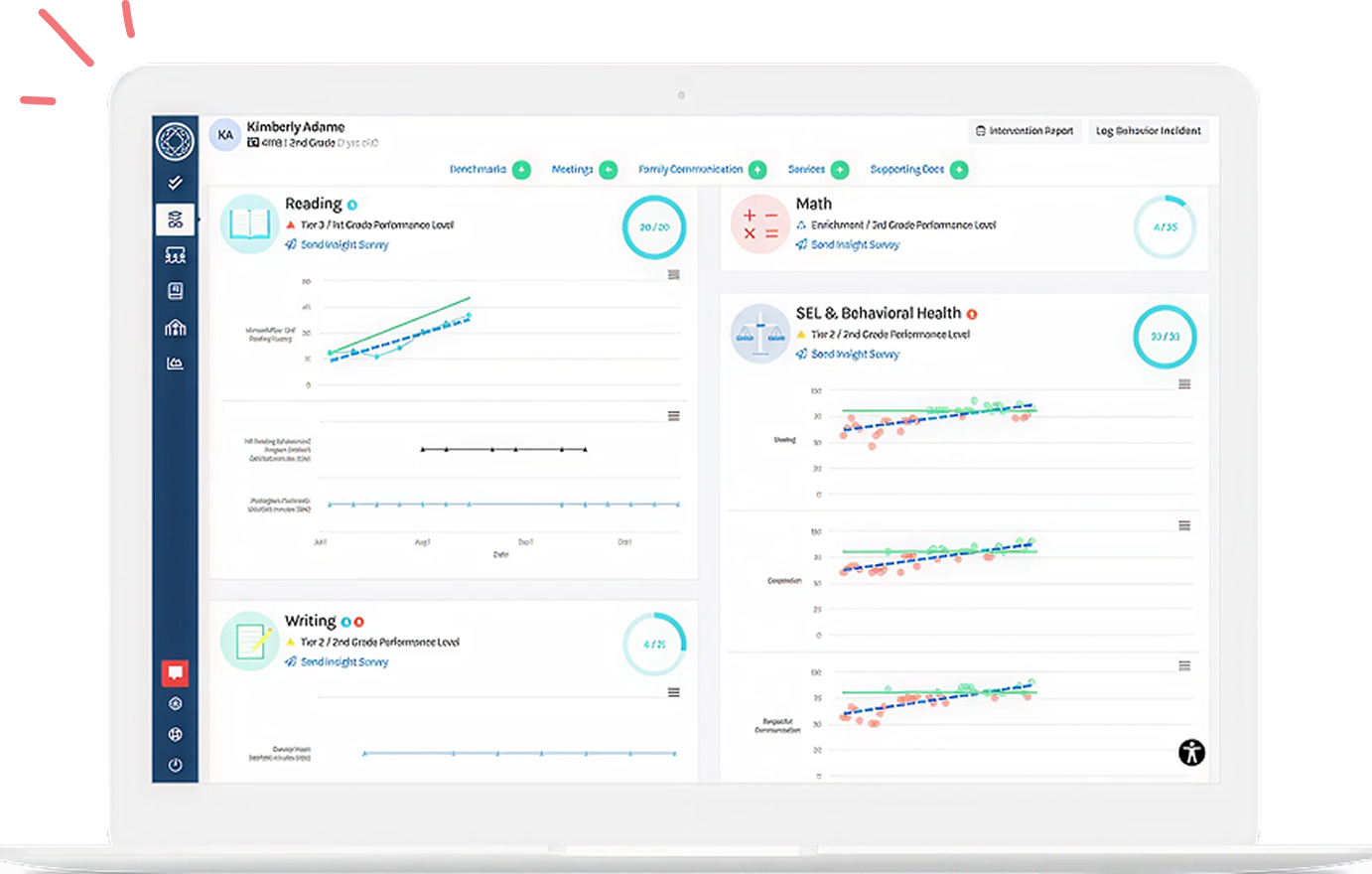

Connecting CCSS to MTSS

![]() Around the time CCSS was developing, Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS) also took shape. A Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) is a framework that helps educators utilize data to identify students’ needs and intervene with the appropriate level of specificity and intensity so that all children have increased opportunities to achieve grade-level mastery. Not surprisingly, CCSS and MTSS arose simultaneously, as both were a response to NCLB, a federal mandate issued to identify and support struggling students. Common Core supported the generation of rigorous curricula, and MTSS was a framework that empowered educators to use data to assess the impact of the curriculum and adjust their practices based on how students perform.

Around the time CCSS was developing, Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS) also took shape. A Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) is a framework that helps educators utilize data to identify students’ needs and intervene with the appropriate level of specificity and intensity so that all children have increased opportunities to achieve grade-level mastery. Not surprisingly, CCSS and MTSS arose simultaneously, as both were a response to NCLB, a federal mandate issued to identify and support struggling students. Common Core supported the generation of rigorous curricula, and MTSS was a framework that empowered educators to use data to assess the impact of the curriculum and adjust their practices based on how students perform.

At the Core

MTSS hinges on the idea that all students should be taught a high-quality, evidence-based curriculum at Tier 1. Research suggests that standards-based instruction correlates with higher achievement (Craig, 2011); most published curricula now align with the CCSS. Most publishers also advertise research linking their programs to positive academic outcomes. When students learn skills as directed by a high-quality, evidence-based curriculum, at least 80 percent of students should be able to demonstrate mastery of the standards by the end of the unit. This suggests that there will always be outliers that do not respond to the standard treatment (Brown-Chidsley & Bickford, 2015). Historically, teachers would move on to the next lesson, even if some students did not master the skill taught. Within an MTSS framework, however, teachers rely on data to determine if students did or did not respond to instruction.

Aligning Standards and Assessments

![]() So…how are standards aligned with assessment sources? Several kinds of assessments are used to inform instruction at Tier 1:

So…how are standards aligned with assessment sources? Several kinds of assessments are used to inform instruction at Tier 1:

State Tests: Almost all state tests align with CCSS, and students must take these tests annually. It sometimes takes months to get this data back, but the information can be very powerful.

- Reports reveal teacher, grade, and school-level performance scores that can be disaggregated by the standard.

- Teachers can determine which skills students failed to master and use that information to adjust instruction in the next year.

- Additionally, a teacher may look at the data of their current class to determine if any prior year skills need remediation for a small group or even the whole class before teaching a grade-level standard.

Diagnostic Screening Assessments: One tenet of MTSS is that teachers should not wait until the end of the year to determine if students demonstrate grade-level mastery. Students take diagnostic screening assessments three times a year, which helps school teams identify struggling students and intervene more quickly. Most testing companies also align their assessments to the CCSS and will generate specific student, class, and grade-level reporting that specifies which skills need further attention. Teachers can review these reports when planning lessons to build small groups for differentiation.

- Differentiation allows teachers to continue to align instruction around a grade-level standard but makes space to meet students where they are.

- Flexible grouping means students complete several different tasks during an instructional period; one task may be independent, one may be a small group activity, and another may be teacher-led. Each student is challenged at their current performance level to optimize engagement.

Ultimately, all students are working towards grade-level performance, but a teacher can be more specific in their support because the diagnostic tool offers more clarity into how students are performing.

Curriculum-Based Assessments (CBAs): As previously discussed, publishers create instruction programs that align with the Common Core. Within each unit of study, these programs often include pre- and post-assessments to determine student grouping and instructional outcomes. The more advanced programs include digital remediation tools for students whose pre-tests reveal they are not ready to access grade-level skills. CBAs are the most frequently delivered of the assessments at Tier 1 and can be instrumental in informing what a teacher does at Tier 1.

For the Students That Fall Behind

How can teachers utilize the CCSS to support children who are struggling to master standards? It starts with embracing a growth mindset, and continually building on previous skills. In CCSS, each skill — for the most part — exists on a continuum. When we see growth as the goal, instead of just reaching benchmarks, supporting struggling students will be less overwhelming and make more sense.

Consider this chart of Common Core math standards from the Ohio State Board of Education, which illustrates how math skills build and develop as students move through grade levels.

- For example, students in first grade work on the following skill: Represent and solve problems involving addition and subtraction. 1.OA.1. Use addition and subtraction within 20 to solve word problems

- Subsequently, second graders build on that skill by working on the next logical step in addition and subtraction, with increased complexity: Represent and solve problems involving addition and subtraction.2.OA.1. Use addition and subtraction within 100 to solve one- and two-step word problems

The skill of adding and subtracting is the same, but the first grader is working with up to 2 digits, whereas the second grader is working with up to 3 digits and multiple steps. Why is this relevant? Because if a student has not mastered previous grade standards on this continuum, we know they will not be able to master the more complex grade-level standards until this deficit is addressed.

For those students who need help with earlier skills or have not demonstrated mastery over grade-level skills, additional instruction beyond the core is required. MTSS requires that all students continue to receive instruction at Tier 1, but some students will also require supplemental instruction to address missing skills.

For those students requiring Tier 2 Support:

- They may receive this instruction in class with the general education teacher or in an alternate setting with an instructional specialist.

- The individual providing the intervention can re-teach or provide additional practice opportunities for a standard taught in the classroom.

- They may choose to work on the grade-level skill or an earlier grade-level skill depending on what the assessment data reveals about students' current performance levels.

| This principle also applies to enrichment practices for gifted students, such that students may begin working on a similar standard for future grades. |

For students requiring intensive Tier 3 and/or special education support, who are often more than one grade level behind their peers:

- Interventionists must focus on foundational skills needed to progress toward grade-level mastery.

- Students should still receive grade-level core instruction.

- The time outside the typical academic instruction period may focus on mastering a standard with accommodations or mastering a power standard but not the sub-standards.

- For the students significantly behind, teachers may determine that demonstrating the basic skills outlined in the “power standards” would be sufficient to keep the student moving forward without becoming overwhelmed.

Power standards are umbrella skills that reflect broad performance. Sub-standards are more specific and nuanced and may require higher-level abstract reasoning.

Accelerated Learning

For schools with large numbers of students requiring Tier 2 or Tier 3 support, an accelerated learning approach using power standards can help map out the pacing for curriculum within a semester or year. Many districts and schools adopt power standards as a way to prioritize learning, making it more reasonable for the teachers to move through the curriculum.

Where are we today?

As I shifted my practice from traditional compliance or completion-based grading to standards-based grading, I noticed that my students better understood learning objectives. They could see how they were growing and were more focused on specific skill areas. My conversations with parents were easier as well because areas of need were clear and specific. When it came time for spring assessments, I was more confident in preparing students because I knew exactly what to focus on.

And, the work did not end there. A focus on standards changed how I structured my lessons moving forward. My team designed more robust and specific assessments, providing us with clear, meaningful data. Now we could identify the students who were falling behind and provide interventions targeted to their specific skill deficits.

Standards-based grading goes hand-in-hand with your Multi-Tiered System of Supports. Contact Branching Minds today to find out more about how we can help make your MTSS vision a reality.

Key takeaways from this article:

- Standards-Based Grading and MTSS share the same goal: clarity, transparency, and accountability around student performance.

- There are a wealth of assessments and curricula that align with the Common Core and effectively inform teacher instruction.

- All instruction should tie to the CCSS with the goal of providing multiple opportunities for students to progress and demonstrate mastery.

Recommended reading:

- Standards-based grading and reporting will improve education

- Seven Reasons for Standards-Based Grading

Citations

Bidwell, A. (2014). The history of common core state standards - US news & world report. Retrieved March 7, 2023, from https://www.usnews.com/news/special-reports/articles/2014/02/27/the-history-of-common-core-state-standards

Brown-Chidsey, R. (2016). Practical handbook of multi-tiered systems of support: Building academic and behavioral success in schools. New York: The Guilford Press.

Craig T. A. (2011). Effects of standards-based report cards on student learning. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://repository.library.northeastern.edu/files/neu: 1127

Geer, W. (2017). The 50-year history of the Common Core. The Journal of Educational Foundations (Fall 2018): 100-117 Retrieved March 6, 2023, from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1212104

Guskey, T. R. (2011). Five obstacles to grading reform. Educational Leadership, 69(3),16-21.

About the author

Branching Minds

Branching Minds is a highly respected K-12 services and technology company that leverages the learning sciences and technology to help districts effectively personalize learning through enhancements to their MTSS/RTI practice. Having worked with hundreds of districts across the country, we bring deep expertise in learning sciences, data management and analysis, software design, coaching, and collaboration. Combined with our extensive toolkit of resources, PD, and technology, we provide a system-level solution. We are more than a service or a software provider, we are partners who will deliver sustainable results for educators, and a path to success for every learner.

Your MTSS Transformation Starts Here

Enhance your MTSS process. Book a Branching Minds demo today.

.png?width=318&height=279&name=DA-Top%20(4).png)

.png?width=716&height=522&name=Tech-Learning-Most-Influential-Edtech-Product-2025(preview).png)