I will never forget one of the toughest phone calls with a parent in my first year of teaching. As soon as the phone call ended, tears streamed down my face. It had taken everything I had to hold together, while a parent listed all the things I had been doing wrong with her child. As a first-year teacher, I understood how to create engaging lessons. I prioritized building relationships with students, but working with parents and families was much more challenging.

|

Key takeaways from this article:

|

As I think back to that conversation, my administrators were supportive, but what I needed was a relationship with the parent. I wanted the parent to know I was calling because I cared about their student, but I hadn’t built up a reserve of previous positive interactions and connections that I could draw on. They had only heard that something was wrong with their child. Now years later, I understand perhaps both sides might have assumed the worst of each other. Maybe, I assumed the parent was unaware and did not care about their child. Perhaps they assumed I didn’t care about their child.

Psychologists explain that in efforts for our brains to make sense of an uncertain or uncomfortable situation, we fill in the gaps with a story, most often negative, as a way of self-protecting. This is called a negativity bias. For example, when we haven’t talked to a friend in a while, we may assume they are mad at us. Perhaps you get the dreaded email from the front office to meet with the principal, who you rarely see in the halls. You imagine a story to make sense of the situation, and your brain tends to put a negative spin on it.

We tell ourselves stories like this in the absence of relationships. As educators, it is easy to make assumptions about families, and vice versa. This kind of bias can affect our connection with families, a connection vital to the work of supporting students.

Why Is Communication With Families Important for MTSS Success?

A Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) is intended to address the needs of the whole child, and we cannot talk about serving the whole child without considering the family. Schools should inform and partner with families about plans and progress with interventions. Many parents only have the framework of their own school experience to understand how school works, and they may need further information. For example, sharing what MTSS is and is not and what support is offered is an excellent way for parents to understand how MTSS helps students. Make an effort to get past the jargon and give them a clear picture of what it means for their student.

At the macro level, building bridges between schools/districts and families is foundational to effective MTSS. Families and communities are important stakeholders in any school district. Communication, by nature, is about building a bridge of understanding and commonality, and communication is one of the foundations of any relationship.

Bridging the Gap Between Home and School |

Some parents may not have time to come to school during the workday or evening. There may be economic factors, language barriers, or experiential barriers. Parents of students with a history of struggle in school may carry that with them each year, hesitant to get involved or let that influence how they view the school and educators. “Educators must make it clear to families that it is their duty to be the first to establish goodwill.” (Dugan, 2022) In this case, bridges of understanding and relationship may need to be repaired or built to help parents engage in their students' support at school. In service of student needs, often the school must make all the effort to build that bridge.

Leaders can set the stage for bridge building by proactively communicating that everyone is on the same team, here to help students, with an open door policy and a positive tone. Setting clear communication expectations will help avoid missteps and misunderstandings.

So, what might this look like at the school or classroom level? Here are a few reminders and ideas to help foster positive relationships with parents and families and combat the effects of negativity bias.

1. Build Positive Communication Into the Everyday Life of the School |

Part of the work we as educators have to do to build the bridge of communication is to make communication routine, positive or challenging. Parents should expect to hear from schools, not just school-wide messaging, but regular phone calls or emails from teachers. For example, an email or call about a student needing a Tier 2 intervention should not be the first time the parent learns about their student’s performance. The first contact with parents should be positive to establish a relationship foundation.

Communication should be as regular as every other routine in the classroom. Within the classroom, practicing the ratio of 5 positive interactions to 1 negative influences student behavior, which can also apply to adult interactions as well.

Administrators can help their teachers with this, regularly communicating with parents and providing time for contacting families within work days or meetings. Leaders can also set expectations for the staff and model them.

👉 Practical Tips:

- Build time in a faculty meeting for teachers to send 1 or 2 emails or messages to parents

- Use templates for email, letters, and phone calls to make communicating easier

- Weekly newsletters from the principal set a tone of messaging from the school

- Practice at least a 3:1 ratio for positive vs. negative contact; 5:1 is better

2. Assume Families Are Doing the Best They Can |

Parenting and caring for a family is hard work. Many parents manage full-time jobs, student activities, and many modern-day stresses. When their student is struggling, this adds to their worries. Start with the assumption that parents want good things for their children. They want them to be successful in gaining the skills they need to go to college, get a job, or have a career. We often bring our unfounded stories about students and their families into the equation. Instead, strive to get to know the student and their family; you might learn more about them, what they bring to the table, and what unique challenges they face.

👉 Practical Tips:

- Greet families at pick-up or drop-off line to build rapport

- Attend school or community events to meet parents and families

- Be curious and ask meaningful questions about students

- Listen more than you talk

3. Communicate in a Way That Works for Families |

There is no perfect formula for communicating with parents; each community and grade level is different, and each community is different. As an educator, it is essential to determine what works best for your families.

Technology now allows for so many ways to be flexible; virtual tools can help remove barriers to communication such as time, location, and efficiency. Technology can also help build more inclusive communication methods. Be sure to follow any protocol laid out by your district to ensure boundaries and privacy are maintained.

👉 Practical Tips:

- Use apps like Remind or Google Voice to make communicating easier for parents that have different schedules

- Offer the option of virtual meetings when parents have trouble getting to the school.

- Provide translated messages, emails, and newsletters to consider multi-lingual families.

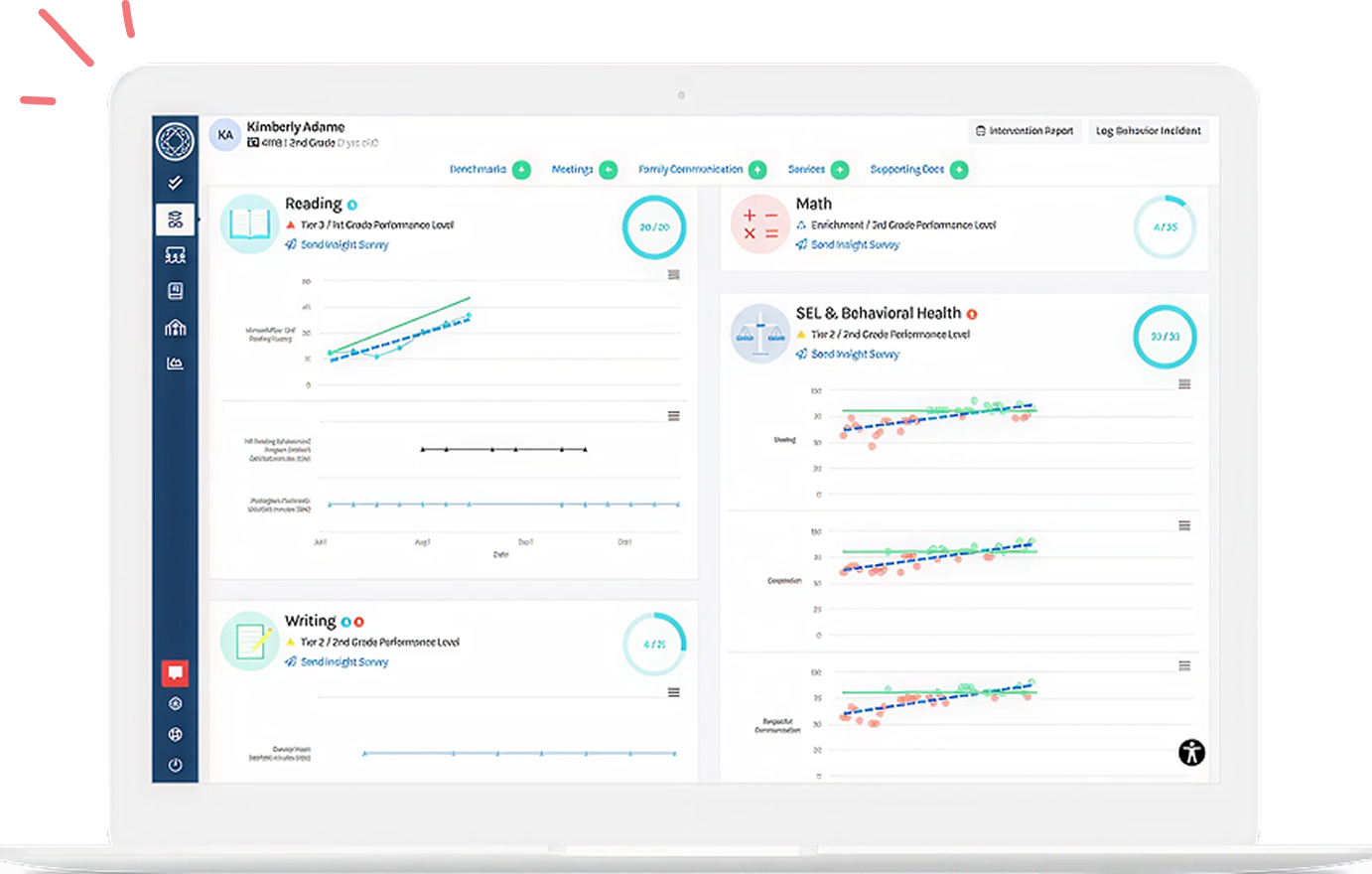

- Use a parent contact log. A streamlined online log such as the one built into the Branching Minds platform allows teachers to see an outline of all family communication taking place, whether by phone, email, or in-person, helping ensure that contacts are meaningful and are not redundant for parents.

4. Invite Families To Be a Part of the Process |

“When families and educators do come together and brainstorm answers around a central question in a way that nurtures dialogue and shared ownership, the solutions are always richer.” (Dugan, 2022) Families are a valuable resource when it comes to problem-solving within MTSS and making intervention plans for a student; they bring insight into a student's life that the school does not. Proactively helping them understand what and why the school offers, such as core curriculum, services, and intervention support for students, will help eliminate confusion or misunderstanding.

At the beginning of the school year, a great way to get to know your students as unique individuals and learners is to hear about them from their families. The back-to-school night only allows for so much time to get to students. At the secondary level, a teacher typically has many students to get to know. Teachers have access to the school databases for surface information, but learning more about a student and their interests and past experiences in school requires some effort.

A grade-level cross-curricular team may want to have one teacher send a survey to parents while another survey the students. You don’t want to overwhelm parents with too much communication or duplicate work, so collaborate with colleagues and be mindful of information overload.

👉 Practical Tips:

- Send out classroom parent surveys to collect insight about students

- Create a shareable live calendar that is continually updated

- Invite feedback from the community, parents, and students about important issues and events

- When a student is struggling, consult with parents first as a part of gathering information

5. Partner With Students in Communication |

When possible, having students be a part of the communication with parents allows students to reflect on their learning and present that to their parents. Giving student agency through student-led conferences has become a way for students to participate actively in learning reflection and setting goals. Research shows that when students participate in setting goals, they are more engaged in learning and have better outcomes. This is also effective for helping students see parents and teachers on the same team and feel supported by both.

For important information, double up on the communication, and send paper fliers and digital ones. Information can get lost at the bottom of backpacks or in a spam folder. For older students, keeping them in the loop through communication emails or phone calls is a way to ensure that there is nothing lost in translation.

👉 Practical Tips:

- Conduct student-led conferences

- Allow students to participate in setting goals for growth

- Attach student emails to communicate home about progress when possible

In the End...It's About Working Together To Support Students

Partnering with families in students’ success takes hard work and intentionality. It requires owning ways that communication has been done poorly in the past and confronting our own negative biases or other barriers to building relationships with families.

Within the MTSS process, helping a student succeed is a team effort. Collaborating and partnering with families is a way to communicate their value in the process of supporting students. As much as educators invest in young people’s lives, their families invest even more. Our common goal is supporting student lives, now and in the future. Don’t fall prey to negativity bias due to a lack of connection.

It is worth examining and improving how we build positive relationships with our students and their families. Those relationships have to power to drive engagement and success!

Having a communication plan is essential to the MTSS process. Learn more from these resources about communicating MTSS.

- RESOURCE BANK: A "BANK" of MTSS Family Connection Resources for Educators

- WATCH this Webinar about Communicating MTSS Vision to All Stakeholders

- READ this blog about Communication Planning for MTSS

- GUIDE for Communicating MTSS with Families and Communities

Sources

Dugan, J. (2022, August 29). Co-Constructing Family Engagement. ASCD. Retrieved September 22, 2022, from https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/co-constructing-family-engagement

Greater Good in Education. (n.d.). Positive Family and Community Relationships. Greater Good In Education. Retrieved September 21, 2022, from https://ggie.berkeley.edu/school-relationships/positive-family-community-relationships/#tab__2

Moore, C. (2019, December). What Is The Negativity Bias and How Can it be Overcome? PositivePsychology.com. Retrieved September 21, 2022, from https://positivepsychology.com/3-steps-negativity-bias/

Rowe, D. A., Mazzotti,, V. L., Ingram, A., & Lee, S. (2017). Effects of Goal-Setting Instruction on Academic Engagement for Students At Risk. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 40(1), 25-35. https://doi.org/10.1177/2165143416678175

About the author

Larissa Napolitan

Larissa Napolitan is the Content Marketing Manager at Branching Minds and host of the Schoolin’ Around podcast, where she spotlights innovative voices and practices shaping education today. A former middle school teacher and instructional coach, Larissa draws on her classroom experience to create meaningful content that connects research, storytelling, and practical insights for school and district leaders. She is passionate about amplifying educator voices and supporting the growth of all students.

Your MTSS Transformation Starts Here

Enhance your MTSS process. Book a Branching Minds demo today.

.jpg?width=716&height=522&name=Better%20MTSS%20Meetings%20Blog%20(preview).jpg)

.png?width=716&height=522&name=The%20Power%20of%20Good%20Data%20(blog).png)