Throughout all of the challenges of the past few years, my thoughts kept returning to the Chinese proverb, “Sāi Wēng lost his horse.” For those of you who haven’t heard it before:

Sāi Wēng lived on the border, and he raised horses for a living. One day, he lost one of his prized horses. After hearing of the misfortune, his neighbor felt sorry for him and came to comfort him. But Sāi Wēng simply asked, “How could we know it is not a good thing for me?”

After a while, the lost horse returned with another beautiful horse. The neighbor came over again and congratulated Sāi Wēng on his good fortune. But Sāi Wēng simply asked, “How could we know it is not a bad thing for me?”

One day, his son went out for a ride with the new horse. He was violently thrown from the horse and broke his leg. The neighbors once again expressed their condolences to Sāi Wēng, but Sāi Wēng simply said, “How could we know it is not a good thing for me?”

One year later, the Emperor’s army arrived at the village to recruit all able-bodied men to fight in the war. Because of his injury, Sāi Wēng’s son could not go off to war and was spared from certain death.

In 2015, when we kicked off this work, over 60% of American 4th and 8th graders were reading and doing mathematics below grade level expectations…well before the pandemic. During that time, most district leaders we spoke to had never heard of MTSS—maybe they were familiar with RTI, but typically only understood it as a way to identify students in need of a special education referral. Even more rare was a district that understood RTI/MTSS to be a framework to achieve all of their district’s goals instead of merely a compliance system. Even as the academic community was lighting up with excitement about the promise of MTSS, there were very few opportunities for practitioners to connect and support each other in this work. This is no longer the case.

It is true that the disruptions to learning caused by the pandemic have shone a bright spotlight on problems that have been facing our schools for decades. It is also true that the pandemic significantly exacerbated these preexisting conditions. Yes, early data reveals widespread learning loss and lower academic achievement across subjects, with the steepest declines among low-income and Black and Hispanic communities. Yes, we are also seeing a sharp and startling rise in youth mental health problems, including increased depression, anxiety, and suicidality. Yes, students are not the only ones struggling in the wake of the pandemic—teachers and administrators have been leaving the profession in droves due to burnout and stress. And yes, the staggering loss of seasoned educators over the past several years has resulted in a nationwide shortage of teachers and administrators at a time when they are needed most.

But what is also true is that in response to the urgency of the moment, there has been a rallying cry from policy-makers, practitioners, researchers, and mission-driven companies that “we can do better, indeed we must,” and a renewed commitment to strengthening systems of support for students, teachers and the education system overall.

These days it is rare for us to meet with a district that is unfamiliar with MTSS—in fact, many districts have hired Directors or Coordinators of MTSS, have recognized how deeply tied it is to all of their goals for both staff and students, and are positioning the work as a framework for supporting all aspects of education.

This December, nearly 1000 educators came together from 48 states and 5 countries for a 2-day MTSS summit Branching Minds hosted. Dozens of presenters—from academic researchers to district administrators to current and former educators—shared their experiences and offered strategies for building strong, collaborative, and scalable MTSS practices. As I listened to these experts share their wisdom, and watched the chats light up with insightful questions and comments, I marveled that MTSS is not just a framework anymore; it has become a movement. We all, collectively, are part of this movement in education toward a more holistic, inclusive, and collaborative. And this gives me great hope that the past few years of hardship may, in fact, lead to something good for education.

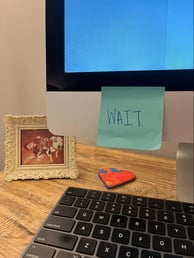

So with all the challenges of the past few years, I remember Sāi Wēng: “How could we know it is not a good thing or a bad thing?” Perhaps it is neither and both. Perhaps it is just the chapters of evolution. And with all change, I continue to work on the meditation to “hold it all lightly,” observe, stay curious, and as the post-it note on my desk this year says, “Wait.” Not to do the work that needs to get done; we cannot wait for that, but “wait” to draw conclusions, because the end of these stories is nowhere near in sight.

So with all the challenges of the past few years, I remember Sāi Wēng: “How could we know it is not a good thing or a bad thing?” Perhaps it is neither and both. Perhaps it is just the chapters of evolution. And with all change, I continue to work on the meditation to “hold it all lightly,” observe, stay curious, and as the post-it note on my desk this year says, “Wait.” Not to do the work that needs to get done; we cannot wait for that, but “wait” to draw conclusions, because the end of these stories is nowhere near in sight.

The momentum for MTSS is powerful; we are building communities, we are proving the impact, and we are winning over the disenchanted and dubious. This work has become a movement and our time is now. I believe 2023 will be a year of significant growth for this work we care about and, in turn, the staff and students we support. So let’s hold our convictions close, reset and recharge. We will need our energy to move this work forward in sustainable ways, but I feel more encouraged than ever before that we have the winds in our sails to get us further and faster than we have ever gone.

Happy Holidays and Happy New Year!

Yours in learning,

Maya

Comments (0)